Free downloadable resources:

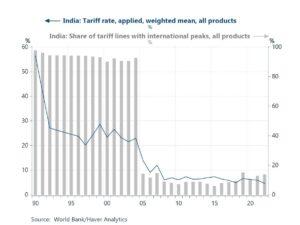

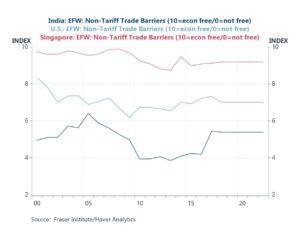

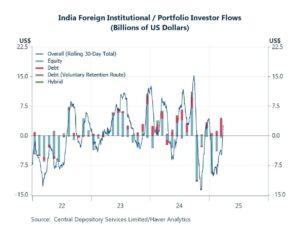

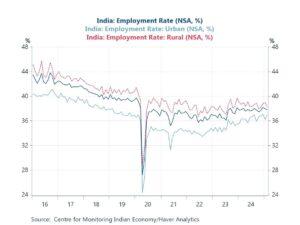

This week, we turn our focus to India in the context of US President Trump’s upcoming “Liberation Day” tariff announcements on April 2. Investors are likely on edge, uncertain about the specifics of Trump’s proposed “reciprocal” tariffs. However, early indications suggest that initial concerns may have been overstated, with significant impacts likely limited to only a handful of economies. As we noted in our previous letter, India could be among the most exposed in Asia to these tariffs, given its relatively high tariff rates (chart 1) and specifically those on imports from the US. Beyond tariffs, India also maintains comparatively high non-tariff trade barriers—both in contrast to the US and its more trade-liberal Asian peers (chart 2). Despite these concerns, India’s financial markets have demonstrated strong performance lately. The Indian rupee has staged a strong recovery from earlier selloffs, while equities have rallied (chart 3). The rupee’s resurgence may be partly driven by seasonal flows, whereas equities appear to have benefited from a sharp rebound in foreign portfolio inflows (chart 4). Looking at longer-term structural challenges, one area where India has yet to fully capitalize is its workforce. Despite a relatively young population, a significant portion remains unemployed (chart 5). A closer examination reveals several contributing factors, including insufficient job creation, a persistent skills mismatch, and, more fundamentally, the need for improved access to basic education (chart 6), among other challenges.

US “reciprocal” tariffs

As discussed in last week’s economic letter, India is among the most exposed countries in Asia to US President Trump’s upcoming “reciprocal” tariffs, set to be unveiled later this week (April 2). This exposure stems from the fact that not only does the US run a significant trade deficit with India, but India also imposes comparatively high tariff rates on imports in general, and not just from the US, as shown in chart 1. While there are concerns about the potential impact of these tariffs, India has already begun trade deal talks with the US to mitigate the effects if they are implemented. It seems that Trump’s underlying strategy may be working: US-India trade talks are reportedly progressing well, with India considering tariff reductions or even eliminations on more than half of its imports from the US.

Chart 1: India’s trade tariffs

|

To provide historical context for India, the country has consistently maintained relatively high import tariff rates due to its desire to protect domestic industries. While it is understandable that tariffs are often used to protect domestic industries, the approach can have drawbacks. For example, sustaining high tariff rates can also lead to scrutiny from trading partners. This, in turn, may provoke retaliatory actions, as seen in the case between the US and India. Furthermore, while the intention behind high tariffs is to protect domestic industries, they may inadvertently stifle competitiveness and productivity. By maintaining high tariffs, India risks trapping its industries in a cycle of inefficiency, while also keeping domestic consumers dependent on local producers, even when better alternatives are available elsewhere. This ultimately prevents local producers from effectively competing with foreign counterparts. All of the above discussion also applies to India’s non-tariff trade barriers. These barriers are comparatively higher than those of the US. They are even more restrictive compared to trade-liberal Asian economies like Singapore, as shown in chart 2.

Chart 2: India’s non-tariff trade barriers vs. US and Singapore

|

Financial market developments

Despite the looming threat of the US’s “reciprocal” tariffs, recent developments in India’s financial markets have been encouraging. The rupee has appreciated significantly, and Indian equities have rallied, as shown in chart 3. This rally marks a dramatic turnaround from earlier this year when the rupee was heavily sold, making it the worst-performing Asian currency for a time. However, the rupee’s recent strengthening may be driven by seasonal factors, such as corporate repatriation of earnings ahead of the fiscal year-end in March, rather than a fundamental shift in its outlook. As for equities, prior steep sell-offs may have attracted bargain hunters, including foreign investors, propping up prices. This trend will be discussed further below.

Chart 3: Indian rupee and Sensex equity index

|

Looking at recent trends in portfolio flows for India, foreign institutional and portfolio investors heavily sold off Indian equities during the first two months of the year, while moderately increasing their holdings in Indian debt, as shown in chart 4. However, more recent data suggests a remarkable turnaround in portfolio flows, with India’s rolling 30-day total indicating a shift from the steep outflows earlier this year. This change is likely due to Indian equities becoming more attractive as valuations dropped during the selloffs. Additionally, the growth-friendly stance adopted by India’s central bank (RBI) under its new governor has likely contributed to the shift in investor sentiment towards Indian equities, with investors now anticipating the next RBI rate cut in April.

Chart 4: India portfolio flows

|

Longer-term structural issues

Shifting focus from trade to longer-term structural issues, while India continues to benefit from a relatively young and growing workforce, it is far from utilizing this potential to the fullest. As shown in chart 5, India suffers from extremely low employment rates, of under 40%, with rural unemployment being even worse than urban rates. This suggests that while the economy has a large pool of ready workers, a significant portion of them remain untapped for economic growth—at least officially. There are several reasons for India’s chronically low employment rate. One key factor is that the growth rate of India’s working-age population significantly outpaces the rate of domestic job creation. This issue is further exacerbated by the fact that most job creation in India is concentrated in the services sector, which is not labour-intensive. Another contributing factor is the severe skills mismatch within the workforce. Many educated working-age Indians find themselves in jobs unrelated to their training, reflecting deeper issues within India’s education system. Lastly, the informal sector poses another challenge. Working-age Indians employed there may not always be fully captured in labour statistics due to challenges with measurement and data collection.

Chart 5: India’s employment rate

|

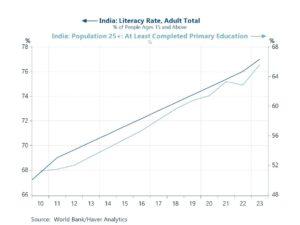

Delving deeper into the structural issue, a two-fold solution seems viable, although achieving it will likely be difficult and take time. First, on the labour demand side, India should focus on increasing job creation, particularly in formal roles and labour-intensive sectors, to absorb the ready pool of working-age Indians. Part of this effort would involve attracting more foreign firms to establish operations and create jobs domestically. Second, India needs to reform its education system to better align with industry needs by emphasizing skills in demand. This would also require improving the overall access and quality of basic education (chart 6), which is essential for working-age Indians to acquire the technical skills and higher education needed in the market. While India has already begun implementing some of these solutions, much deeper reform is still needed to realize their full potential.

Chart 6: India’s adult literacy and basic education rate

|

Join our mailing list to know when our latest Economic Letter from Asia and Charts of the Week are released.

Browse all our database offerings here.

Comments are closed.