Talking China

In this week’s letter, we focus on China. The Chinese economy has shown early signs of a pickup in recent weeks, following a series of easing measures. However, these signs do not yet suggest a full-scale economic rebound, and observers remain uncertain about whether the economy will meet its 5% growth target for the year. We also explore China’s latest debt swap program for local governments, which many see as a positive step. Nonetheless, some are underwhelmed by the scale of the RMB 10 trln program, which is small compared to the estimated size of local governments’ “hidden debt”. In addition, we address broader structural issues likely to continue as points of contention between China and other major economies, and most notably the US. Issues include China’s persistent current account surplus and concerns about its overcapacity. We examine the potential impacts of this overcapacity, from its detrimental effect on domestic industries in receiving economies to the deflationary pressures from Chinese exports. Additionally, we touch on the financial flows resulting from China’s export revenues. Finally, we end on a more positive note, highlighting China’s progress in its green energy transition, with some forecasters predicting that China will reach peak carbon emissions within the next year or two.

Recent developments

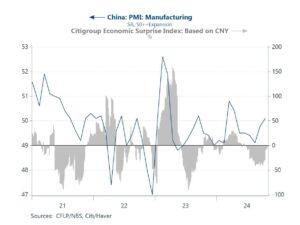

The Chinese economy has picked up pace in recent months, following a series of easing measures introduced by authorities. These measures include interest rate cuts, relaxed property restrictions, and, more recently, a debt swap program for local governments. Of particular note is the official manufacturing PMI, which has returned to expansionary territory (Chart 1) for the first time in six months. More broadly, the economic surprises from China have shifted back to more neutral levels, following a period of disappointing results. However, while there are encouraging signs of a turnaround, these developments do not yet point to a full-scale economic rebound.

Chart 1: China’s official manufacturing PMI and economic surprise readings

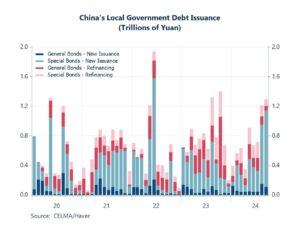

Delving deeper into China’s debt swap program for local governments, the plan will raise the debt ceiling for special bonds by RMB 6 trln ($830 bln) over the next three years, enabling local governments to refinance the “hidden debt” accumulated through Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs). Additionally, local governments will be allowed to use up to RMB 800 bln ($110 bln) annually for refinancing LGFV debt over the next five years. Nonetheless, local governments in China have already increased bond issuance in recent months (Chart 2). While the new program is viewed as a positive step, many observers remain underwhelmed by its scale. Despite the RMB 10 trln package being significant, it is still far smaller than estimates of the total “hidden debt” carried by local governments. For instance, the IMF estimates China’s LGFV debt at RMB 60.2 trln as of 2023, projecting it will rise to RMB 65.6 trln in 2024. If these estimates are accurate, the debt swap program would address only a small fraction of local governments’ overall debt burden.

Chart 2: China’s local government debt issuance

Broader structural topics

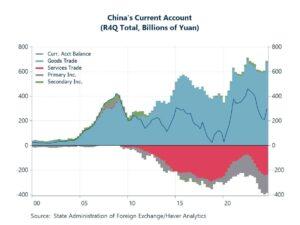

Turning to broader structural issues, China’s current account surplus remains persistent and large (Chart 3), drawing criticism from major economies about the impact of these imbalances on their own economies. While the rebound in outbound tourism by Chinese travelers has helped partially offset China’s significant goods trade surplus by contributing to a services deficit, this has not been enough to fully offset the significant goods surplus. The drivers and consequences of China’s economic imbalances are complex. For example, China’s industrial policies in sectors such as electric vehicles (EVs) have drawn criticism from the US and several European countries. These policies are likely to remain a key point of tension in US-China relations, especially with US President-elect Trump’s imminent return to leadership next year. These economies believe that China’s overcapacity and extensive use of state subsidies distort global markets, to the detriment of their domestic industries. However, China argues that there is no overcapacity, and that its comparative advantage in sectors like EVs is the result of market competition, not government intervention.

Chart 3: China’s current account

Another dimension through which China’s overcapacity is manifesting is in the sharp decline in unit export values, which have been falling for over a year (Chart 4). Key concerns in receiving economies revolve around China’s overcapacity in sectors like steel, home appliances, and electric vehicles (EVs). This overcapacity has led to massive exports of cheap goods that far exceed domestic demand in China. While these exports technically contribute to China’s GDP growth, they are undermining local producers in receiving economies, who struggle to compete with prices that are unsustainably low. This creates a significant challenge for local industries, potentially driving some out of business. Moreover, the influx of inexpensive Chinese goods can lead to deflationary pressures in receiving economies, as falling export prices push down the overall cost of goods and services.

Chart 4: China’s unit value of exports

China’s persistent current account surplus means its substantial export revenues must be reinvested somewhere. A key channel for this reinvestment is the acquisition of foreign assets, with US long-term securities being a major recipient, particularly US Treasuries (Chart 5). The majority of China’s US holdings are in the form of Treasuries, with US corporate equities constituting a much smaller share. In effect, China has been financing the US trade deficit by purchasing US government debt. Over time, China has become one of the largest foreign holders of US Treasuries, second only to Japan. However, it is important to note that China’s holdings of US Treasuries appear to have peaked in the last decade, with its investments in these securities actually declining in recent years.

Chart 5: Mainland China and Hong Kong’s holdings of US long-term securities

Some bright spots

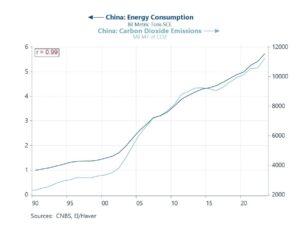

We conclude this week’s letter on a more optimistic note, highlighting China’s rapid progress in its green transition over the past decade. China’s swift development and adoption of green technologies have led many forecasters to expect the economy to reach peak carbon emissions within the next year or two. That said, much of China’s emissions profile, with carbon dioxide as the dominant contributor, remains closely tied to energy demand, which drives consumption (Chart 6). This is understandable, as while China’s green energy transition has been impressive, it remains incomplete, with a significant portion of its energy still sourced from coal. As a result, if China’s energy demand increases—driven by factors such as stronger global demand for manufactured goods—overall emissions could rise again, especially if the impact of its ongoing green energy adoption does not fully offset this surge. However, if China’s green energy transition continues to gain momentum and proves sustainable, we could see a decoupling of the relationship between energy consumption and emissions in the future.

Chart 6: China energy consumption and carbon emissions

Join our mailing list to know when our latest Economic Letter from Asia and Charts of the Week are released.

Browse all our database offerings here.

Comments are closed.